- Rosemary plants typically have stiff, needle-like evergreen leaves.

- Their stems become woody over time, giving the plant a shrubby appearance.

- Rosemary often grows in a bushy or upright form, though some varieties trail.

- It produces small blue or purple flowers, usually in late winter or spring.

- A key identifying feature is its strong, distinctive piney and herbal scent.

- The plant’s appearance can signal its health, especially regarding water levels.

Have you ever been captivated by the look and scent of a rosemary plant? Perhaps you’ve brushed against its leaves in a garden and instantly recognized that unmistakable fragrance. Rosemary isn’t just a culinary staple; it’s a beautiful evergreen shrub that adds texture and structure to the garden. But beyond its well-known aroma, what does rosemary look like up close, and how can its appearance tell you how it’s feeling? Let’s explore the visual characteristics of this Mediterranean marvel and delve into some insights gained from personal gardening adventures (and misadventures!).

Contents

- Describing Rosemary’s Appearance

- Rosemary Plant Facts:

- Rosemary’s Natural Growth Habit vs. Training

- The “Standard” Experiment

- Lessons from Other Bushy Plants

- Red Currant Plant Facts:

- Clove Currant Plant Facts:

- Reading Rosemary’s Signals: What Stress Looks Like

- Thirsty Rosemary

- Overwatered Rosemary

- Bringing New Rosemary Life: Propagation

- Conclusion

Describing Rosemary’s Appearance

Rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus, formerly Rosmarinus officinalis) is a plant with a distinctive look that makes it relatively easy to identify once you know what to seek.

- Leaves: The most striking feature is the leaves. They are small, needle-like, and evergreen, holding their color throughout the year. Unlike many herbs that wilt dramatically when thirsty, rosemary leaves are quite stiff and retain their shape even when dry.

- Stems: As the plant matures, the stems become woody and rigid, especially towards the base. This contributes to its shrubby, sometimes upright, or even trailing growth habit, depending on the specific variety.

- Overall Form: Naturally, rosemary tends to be a bushy plant, sending up new growth from its base. Left to its own devices, it can become quite dense and sprawling, perfect for informal gardens or hedges.

- Flowers: While not its primary feature, rosemary does bloom, typically producing small, often delicate blue or purple flowers. These usually appear in late winter or early spring, adding a splash of color when little else is flowering.

- Scent: Although a scent isn’t a visual trait, the strong, aromatic fragrance released when the leaves are touched is an integral part of identifying rosemary. It’s a rich, piney, and slightly camphorous smell that is instantly recognizable.

Rosemary Plant Facts:

- Scientific Name: Salvia rosmarinus (formerly Rosmarinus officinalis)

- Common Name: Rosemary

- Zone: Typically hardy in Zones 8-10. Needs protection or overwintering indoors in colder climates.

- Light: Full sun (at least 6-8 hours per day).

- Humidity: Prefers low to moderate humidity.

- Water: Drought-tolerant once established; needs good drainage. Susceptible to root rot if overwatered.

Close-up of vibrant green rosemary needles against a blurred winter garden background.

Close-up of vibrant green rosemary needles against a blurred winter garden background.

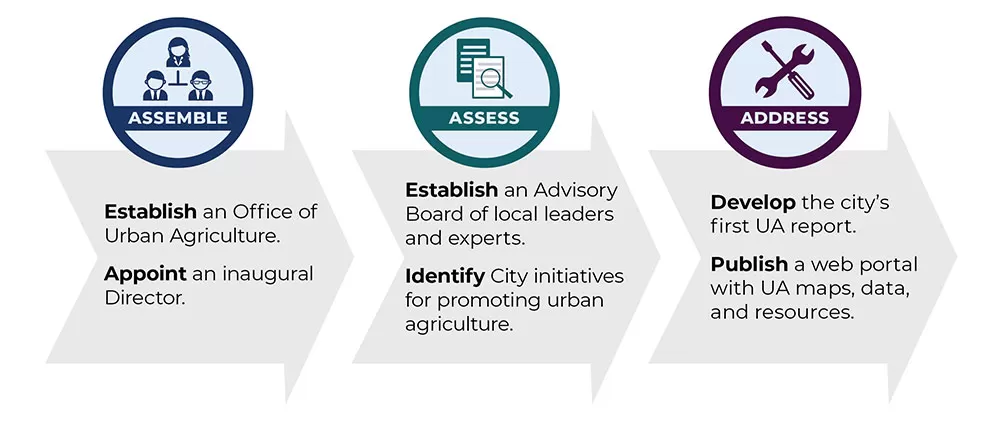

Rosemary’s Natural Growth Habit vs. Training

Understanding how rosemary naturally grows can be key to its long-term success, especially if you’re growing it in a pot. Hailing from the Mediterranean, its roots in the ground can spread extensively to find moisture. In a container, their reach is limited.

Rosemary is a naturally bushy plant. This means it’s genetically programmed to send up multiple stems from the base and potentially spread outwards, with stems layering and rooting where they touch the soil. This bushy structure, however, means its individual stems aren’t typically designed for extreme longevity as thick, singular trunks.

The “Standard” Experiment

Some gardeners, including myself, enjoy training certain plants into “standards.” A standard is a plant that is naturally bushy or trailing, but is pruned and trained to have a single, clear upright stem topped with a rounded ‘mop’ of foliage – essentially, a miniature tree shape. It’s a formal, attractive look, giving a storybook feel. I confess, I’m a “standardophile” and love the neatness and shape.

Collection of potted standard plants, including rosemary, bay laurel, and citrus, showing their trained tree-like form.

Collection of potted standard plants, including rosemary, bay laurel, and citrus, showing their trained tree-like form.

While you can force rosemary into this standard shape, it goes against its intrinsic desire to grow as a multi-stemmed shrub. I’ve personally found that my rosemary standards, beautiful as they were, eventually seem to give out. Their forced “trunk” doesn’t have the natural vigor or lifespan of a true tree trunk, leading to what I call “Rosemary Death Syndrome” (RDS) in these trained forms.

Lessons from Other Bushy Plants

This isn’t unique to rosemary. I’ve had similar experiences with other plants that are naturally bushy but trained formally.

Years ago, I trained a red currant bush into an espalier – a plant trained flat against a structure, like a fence. Red currants naturally sprout from the base. To maintain the espalier, I had to constantly prune away these new base sprouts, forcing all the plant’s energy into two main horizontal “arms” atop a single, trained stem. It was stunning, particularly in July with its jewel-like berries.

Red Currant Plant Facts:

- Scientific Name: Ribes rubrum

- Common Name: Red Currant

- Zone: Zones 3-8

- Light: Full sun to partial shade

- Humidity: Moderate

- Water: Needs consistent moisture; prefers well-drained soil.

I also tried training clove currants (Ribes odoratum) into miniature trees for their incredibly fragrant yellow flowers. Clove currants are even more determined to spread, sending arching stems everywhere. The three little “trees” I created were lovely but, like the rosemary standards, their lifespan was shorter than the natural bush form.

A clove currant bush trained as a small standard tree, showcasing its arching stems.

A clove currant bush trained as a small standard tree, showcasing its arching stems.

Clove Currant Plant Facts:

- Scientific Name: Ribes odoratum

- Common Name: Clove Currant, Golden Currant, Buffalo Currant

- Zone: Zones 4-8

- Light: Full sun to partial shade

- Humidity: Moderate

- Water: Drought tolerant once established.

These experiences reinforced that bushy plants aren’t meant to rely on a single, long-lived stem like a true tree. While training can be done, it may impact the plant’s natural vigor and lifespan compared to letting it grow in its preferred multi-stemmed form.

Reading Rosemary’s Signals: What Stress Looks Like

One challenge with rosemary, as hinted at earlier, is that its stiff leaves don’t dramatically droop or wilt like many other plants when they’re thirsty. This makes identifying distress based on appearance slightly different.

Thirsty Rosemary

If the soil has been too dry for too long, rosemary’s perky leaves won’t suddenly flop. Instead, they may take on a slightly duller, sometimes even a bluish or grayish cast. The most telling sign is when the normally firm, evergreen needles become dry and brittle. If you lightly brush against the stems and dry leaves rain down, the plant is likely suffering from severe drought. While dry needles can mean the plant is dead, sometimes a timely watering can revive a plant that seems on the brink.

Dry, brown rosemary leaves still clinging to woody stems, indicating plant distress or death.

Dry, brown rosemary leaves still clinging to woody stems, indicating plant distress or death.

Overwatered Rosemary

Conversely, rosemary is highly susceptible to root rot if the soil stays too wet. While the leaves may not look overwatered initially, persistently soggy conditions drown the roots. Damaged roots can’t take up water or nutrients, and eventually, the plant will show signs of distress at the top, often looking similar to drought stress – yellowing or browning needles and dieback. The difference is the soil; if it’s wet, the problem is likely too much water, not too little. Finding the right balance is crucial!

Bringing New Rosemary Life: Propagation

Despite the challenges, rosemary is relatively generous and often easy to propagate from cuttings. If you have a healthy plant (or know someone who does!), you can easily start new ones.

Semi-woody cuttings (stems that are firm but not completely hardened) are ideal. Simply snip off a piece, strip the leaves from the lower portion, and place the base into a well-draining rooting medium, such as a mix of peat moss and perlite.

To encourage rooting, warmth at the base (like from a heating mat) is beneficial, as is high humidity around the leaves. Covering the cuttings with a clear plastic bag or an inverted tub creates a mini-greenhouse effect. Place them in bright, indirect light where the leaves can photosynthesize without the cuttings getting too hot. With a little patience, you’ll soon see new roots forming, and tiny new rosemary plants will be on their way!

Several semi-woody cuttings of rosemary and holly in small pots filled with rooting medium, ready for propagation.

Several semi-woody cuttings of rosemary and holly in small pots filled with rooting medium, ready for propagation.

Conclusion

So, what does rosemary look like? It’s a sturdy evergreen with distinct needle-like leaves, woody stems, and a naturally bushy form, often adorned with small blue flowers. Its appearance is closely tied to its health, particularly its water status – watch for bluish hues or dry needles as potential signs of thirst, but also be mindful that too much water is a death sentence. While it can be trained into formal shapes like standards, appreciating and accommodating its natural bushy growth habit may lead to a longer, more vigorous life for your plant.

Happy gardening, and may your rosemary always be fragrant and green!

Have you had success or struggles growing rosemary? What tips do you have for keeping it happy? Share your experiences in the comments below! If you enjoyed this article, feel free to share it with fellow garden enthusiasts.